A THEOLOGY OF SUFFERING AND STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE IN THE CHIN (MYANMAR) CONTEXT

INTRODUCTION

This research is a study of Gustavo Gutierrez’ theology of suffering and

struggle for justice and its relevance to theological reflection in the Chin context.

The people of Myanmar have been on a state of suffering for ages. Suffering

has become a permanent fixture of national life. In the words of Thawng Khuo

Tuong, “There is no justice and peace in the country, peace is like a burning

coal under the ash.”[1] Theosophies and

theologies, both in their formal and popular form have reflected on this state

of national suffering as caused by spirits, divinities, and supernatural forces

reciprocating the people’s failure to behave properly; and that the only proper

way to address the problem of suffering is to properly observe religious

rituals and to behave accordingly. The Christians and the churches, likewise,

reflect theologically along these lines. The churches’ exposures to the social

gospel, if ever there are, have made no dent on their a-political colonial

Baptist missionary theology.

This research saw Gustavo Gutierrez’ theology of liberation as an

appropriate conversation partner in theological reflection in Myanmar,

particularly in the Chin context. His theology of human suffering and the way

to get rid of suffering, which is, struggling with the poor in their struggle

of justice came to the researcher as a relevant theological proposition.

Theologians from Myanmar and Asia have been engaged in this reflection but the

researcher wants to focus specifically on Gutierrez’ liberation theology of

suffering and its impact to local theologies and its relevance to the Chin

people’s collective quest for emancipation from mass suffering.

Suffering in the discussion of Gutierrez include propositions for

praxis. Praxis involves the people of God and the action- reflection of the

people of God on suffering and the struggle to overcome it.

1.1 Background of Study

Dominant theological voices

in the Chin churches are not very responsive to the question of mass suffering

in Myanmar. The few contextual theologians and the theologies that they have

produced have not made significant impact on the churches. Their emphasis, too,

is primarily on the cultural contextuality of theology which was typical to

earlier Asian contextual theologies. This study makes the question of human

suffering as its primary starting point.

Gustavo Gutierrez is

inarguably one of the most influential of all liberation theologians. The

influence of his theology was widespread. Gutierrez sought to discern the

Christian message in relation to the question of human suffering. His theology

of liberation focuses on Jesus not only as Savior but also as Liberator of the

poor and marginalized. Based on the post-world war II social situation of Latin

America where masses of people are suffering due to oppression and injustice,

his theology envisions the liberation of the oppressed from their suffering and

interprets the Scripture through the plight of the poor. His theological emphasis is the glory of God that is

present in and among, and which gives dignity to the poor. In brief, Gutierrez

sought to discern the Christian message in relation to the problem of suffering

in underdeveloped, developing, if not maldeveloped societies.

1.2 Statement of the

Problem

Gustavo

Gutierrez’ theology represents to the researcher a new approach to doing

contextual theology. Gutierrez and liberation theology in general may be half

of a century year-old now and was an influence to Asia and Myanmar some few

decades later but, in so far as the researcher’s faith community is concerned,

the Baptist community in the Chin state, Gustavo Gutierrez and Latin America’s

theology of liberation, wherever they are heard, are still foreign theologies

that are good as a meaningless to the Chin people. It is for the reason that

this study focused more on Gutierrez’s theology of suffering more than focusing

on Latin American theology of liberation in general. Suffering is a central

pastoral concern/theme that can bring in Gustavo Gutierrez as a theological

influence in Chin Christianity.

It

was the researcher’s proposition that Chin Christians need to review their

understanding of suffering and the alleviation of people’s suffering through

the lenses of Gutierrez’s theology of suffering and struggle for justice. This study framed and

furthered the discussion of the conversation between this Gutierrez and the

Chin situation by raising the questions. The general question involves

responding to what is the possible relevance of

Gutierrez’ theology of suffering to the Chin church in Myanmar?

1. What is Gutierrez’ analysis of society?

2. What is Gutierrez saying about suffering and Christian responsibility?

3. What are the popular beliefs about suffering among the Chins in

particular and the people of Myanmar in general?

4. What are contemporary theologies in Myanmar saying about suffering?

5. How can Gutierrez’ theology be appropriated in the Chin context?

6. What does Gutierrez’ struggle for justice within the context of the

church’s preferential option for the poor say about the Chin church and its

participation in the alleviation of people’s suffering?

1.3

Objectives of the Study

The purpose of this study is to reflect on the reality of human suffering

in the Chin (Myanmar) context as an indigenous Chin using Gustavo Gutierrez’

liberation theology as lens. The writer breaks the objectives of this study

down to the following:

1.

To understand Gutierrez’s theology of suffering and how this can be used in the

understanding of the Chin social situation.

2. To conducted a survey of

contemporary theological reflections and popular theologies in Myanmar that are

relevant to the issue of human suffering and its alleviation.

3. To explore the relevance

of Gutierrez’s thoughts to the Chin society and how liberation theology inform

contextual theological reflection in Chin.

4. To propose for an appropriate

Christian response to suffering in the Chin Land in the light of Gutierrez’s

thoughts.

1. 4 Significance of the

Study

This

study offers an alternative view and understanding of suffering based on

Gustavo Gutierrez’ liberation theology - a view that can serve as a critique of

the dominant and popular metaphysical and fatalistic views on suffering among

Chins, ecclesial communities included.

First,

in contrast to the more general horizon of Asian contextual theologians that

include theologians from Myanmar, this study focused and sought to contribute

more on the further development of theological reflections on suffering that is

contextual and relevant to the Chins.

Second,

this study helps introduce a new approach to analyzing and understanding the

Chin (Myanmar) social situation – including the state and situation of Chin

churches.

Third,

this study can help the churches shape models of mission and ministry that can

effectively address the root causes of mass suffering in Myanmar in general and

the Chin state in particular.

Fourth,

this study hopes to generate a process of self- realization for Chin Christians

of their being agents of change in the wider society; and offers hope that the

situation of suffering can be challenged and changed.

1.5 Scope and limitation

This

research is limited to the investigation of Gustavo Gutierrez’s theology of

suffering as applied to the Chin Society. Thus, the research is limited to four

areas of investigation:

1. A study of the historical and

social situation in the Chin state.

2. A study of

popular religious understanding of suffering and the human condition in the

region.

3. A study of

Gutierrez’s view on suffering and Christian responsibility.

4. A study of the

possible implications of Gutierrez’ theology in doing theology in the Chin

state.

1.6 Conceptual Framework

This study reflects on the Chin

people by analyzing the social, economic, political, cultural and some aspects

of Chin society and using Gustavo Gutierrez’ theology of suffering and struggle

for justice as principle and tool of analysis, this study proposed an

alternative Christian discernment and appropriate response to the suffering of

the Chin people.

1.7 Theoretical Framework

In order to support this study, the researcher used Gustavo

Gutierrez’ analysis of historical situations in Latin America. Gutierrez’

liberation theology begins from historical reality and developed from the

perspective of the poor. He contributes to the interpretation of crucial

biblical events Exodus. Gutierrez' understanding of the Exodus is the

narrative's underlying assumption of humans as participants in the making of

their own history. By developing a theology from the perspective of the poor

and by underlining with it the need of Christians to be actively involved in processes

of social change that promote justice. [2]

While, one should understand that when Gutierrez used “suffering” it refers to

the sufferings of the poor. Gutierrez’s work on A Theology of Liberation and The Power of the Poor in History has

described the root causes of human suffering. It is a systemic

institutionalized injustice and oppression of people that results in their

economic and political marginalization. In this systemic exploitative and

oppressive structures of social evils are human construct. [3]

The systemic forms of injustice and oppression are concretely seen

on human beings who are alienated from the products of their labor and acts of

production as they are made into commodities by the market. The concept of

class struggle is tied in Marxist thought with the concept of "mode of

production."[4]

The class struggle presupposes that what is basically wrong and should be

changed in society are the relations of production.

Relations of production refers to human/people’s relation in

connection the possession of tolls/means of productions and participation in

production. Economics is about human relations, in particular it is about class

relations. Class relations are economic relations. The emergence of classes in

society is an offshoot of economic relation, particularly the relations of

production. The division of society into classes is based on the relation of

production. Essentially, the relations of production are division and relation

of classes in production. Classes are vast group of people with different

status in certain economic system based on the possession of tools of

production, participation in production, the amount of share and the way people

acquire the share of the products created by society. The division of society

into classes is a division of the people into exploiters and exploited,

oppressor and oppressed, ruling and ruled.[5]

The root of all sufferings are a sinful structure, this liberation

is reached "only through the acceptance of the liberating gift of Christ,

which surpasses all expectations”[6],

act as new creatures in the love of neighbor and in the effective search for

justice, self-control and the exercise of virtue. Write from the perspective of the suffering in their

contexts and Gutierrez suggestions as to what a fitting response to suffering

should be namely, “Preferential

option for the poor, Education and Conscientization,

Community-Building, and Mobilization.” Gutierrez deep social analysis offers a richer understanding of

human suffering and points to a vision of sustainable social activism and for

all Christians, both the rich and the poor, involves solidarity with the

suffering poor.

1.8

Research Methodology

This research project is

primarily a theoretical research that focuses on three areas: Gustavo

Gutierrez, his theology of suffering and his corollary reflections on the

poor’s struggle for justice; the dominant and popular views on suffering and

the human condition among Chins; and the appropriation of Gustavo Gutierrez’ theology

in the Chin context.

First, the researcher

made an extensive review of the literature of liberation theology, even as this

focused initially and primarily on Gutierrez’s analysis of historical contexts of

suffering and struggle for justice. In this study,

the researcher looked at Gutierrez’s critique of developmentalism and how he

analyzed the cause of mass suffering in Latin America and the third world with

his dependency theory. Following the methodology of Gutierrez, this writer

explored the author’s advocacy for the poor in his now all too popular

phraseology “preferential option of the poor” and his understanding of

ecclesiology and Christian responsibility vi-a-vis suffering and the human

condition.

Second, this study

investigated popular views on human suffering including those from indigenous

religious traditions or the so-called folk beliefs; those from the churches and

Christian communities who were raised under the tutelage of American Baptist

missionaries; and also those from the Buddhists, since Myanmar is officially a

“Buddhist country” and that to some extent the influence of Buddhism also

extends to upland tribal states.

Third, to pursue this, this

writer organized conversations with respondents that are representative of the

communities in the Chin state. This investigation also included a survey of the

works of Myanmar’s leading theologians and their relevance to the thesis of

this study and a solicitation of the current views of Church leaders who may or

who may have not read anything about Asian contextual theologies. These group,

too, were included as respondents to the questions of this research.

The questionnaire raises

questions that purse the objectives of this study. They respondents included

pastors who are immersed in their communities and theologically schooled. These

respondents are also most familiar with the indigenous religious beliefs and

through processes: questions included (1) what is temhtuarnak, suffering to you, (2) what does temhtuarnak include, and (3) what to you is the causes of people’s temhtuarnak?

Fourth, this study

facilitated a dialogue between Gutierrez’ theology of suffering and the

struggle for justice on one hand and the Chin social and ecclesial situations

on the other. This was the point in the study where this writer tried to

appropriate or contextualize Gutierrez’ theology in the Chin context and argued

for the relevance of the liberation theologian to theological reflection in the

Chin context.

In the appropriation of

Gutierrez’ theology, this study contracted the discussion to at least four

themes: the ethics and praxis of the church vis-à-vis suffering, the

“preferential option for the poor” in the Chin context, the struggle of the

Christian and the churches for political and economic justice, and the

constitution of the people of God specific to the Chin setting.

1.9 Definition of Terms

Burmanization: “Burmanization” is a quasi-official policy and a

process that enforces Burmese national consciousness on minority groups,

including the Chins of the tribal/highland states of Myanmar.[7]

Chin: “Chin” came from the root word “Chin-lung.”[8]

According to the myth on the origins of the Chin people, the said people

emerged into this world from the bowels of the earth or a cave or a rock called

“Chin-lung.” According to Lian H Sakhong, Chin is the national name for various

ethno-linguistic groups such as the Asho, Cho, Khuami, Laimi, Mizo and Zomi.

Chin is one of the national groups, albeit, a minority group that help

constitute the predominantly Burmese nation of

Myanmar.

Dingthlu-Lairel: “Dingthlu-Lairel” is a combination of words that expresses the moral

attributes and qualities of God who created all things and ruled over with

righteousness and justice, mercifully and equally to all creation.[9]

Dukkha: Suffering. In Buddhism, Dukkha is used in a broad sense to mean suffering.[10]

It includes not merely physical and mental suffering; it also means

imperfection, impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and ignorance concerning the

true man and his existence. [11]

Gautama: Gautama Buddha, also known

as Siddhartha Gautama or simply the Buddha, was a sage on whose

teachings Buddhism was founded.

Hermeneutics: The task of reflecting on how we go

about doing our interpretation of texts, life and culture.

Karma: The word means actions,

work or deed. It also refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect

where intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that

individual (effect).

Khuachia: The

evil spirit or Lucifer is called khuachia.

Khuachia is the cause of human suffering, accident, sickness, and death on

the life of human beings.

Liberation Theology: Liberation theology is an

interpretation of Christian theology of that emphasizes a concern for the

liberation of the oppressed. Latin American liberation theology is an approach

or a system of doing theology that was

influenced by the political philosophy and/or dialectical materialism of Karl

Marx and progressive political

theologies of the 20th century its starting point is that of Christian/ church

solidarity (“preferential option for the poor”) with the poor and suffering in

their struggle for liberation.

Myanmar: Myanmar was called Burma until the previous

military junta changed it into Myanmar.[12] Since June 19, 1989, Myanmar has been used as

the country’s official name.[13] Most local people and the international media

still casually use Burma instead of Myanmar.

Nirvana:

Central to Buddhist teachings, “nirvana” refers to the

imperturbable stillness of mind after the fires of desire, aversion, and

delusion have been finally extinguished. The Burman Buddhist understanding of “nirvana” is varied. Metaphysically, it means “deliverance from

suffering;” psychologically, it means “eradication of self or egoism;” and

ethically, “nirvana” means the “destruction of lust, hatred and ignorance.”

Orthopraxy: Right way of behaving,

contrasted with orthodoxy, right belief, which is held to be less interested in

the practical demands of faith.

Praxis: A term often used in liberation

theology to describe the actions and commitments which provide the context for

theological reflection. It means the discovery and

formation of theological truths out of a given historical situation through

personal participation in the process of social change.

Relevance: Relevance is a term used to describe

how pertinent, connected, or applicable something is to a given matter.

Sin: According to Gutierrez, is not just

private. Sin is a social, historical fact, that absence of brotherhood and love

in relations among men, the breach of friendship with God and other men; and

therefore an interior personal fracture. While, sin, for Christian Chins, is

the willful disobedience to the law and commandment of God. The source of sin does not lie in material things but in man’s

spiritual rebellion against the sovereignty of God.

Struggle for justice: It is the effort that every unequal and unjust society makes to better

integrate all its members. In Latin America the church struggle with the

poor and justice, equally paying for every person

as their worth.

Suffering: Suffering is

a consequence of human freedom. Free will do good or evil. According to Gutierrez, suffering is

a spiritual and material-history reality. It is cause by the product of

international capitalism, social

injustice, and political repression.

Tatmadaw: The Tatmadaw is the official name of the

armed forces of Myanmar. It is administered by the Ministry of Defense and

composed of the Army, the Navy and the Air Force.

Temhtuarnak:

in Hakha Chin temhtuarnak means

suffering its included ngan-fahnak-

physical suffering and intuarnak-

emotional suffering.

Theodicy: It is the combination of two Greek

words, “theos” (god) and “dike” (justice).

Theodicy, thus, means explaining the goodness of God

and the presence of evil.[14]

The

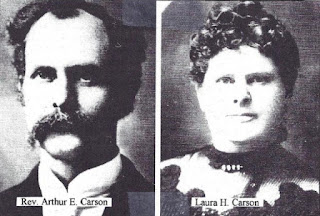

Chin Church: The first American Baptist missionary

to the Chins was Arthur Carson and Laura Carson reached Hakha on March 15,

1899. Through the works of the missionaries several Christian churches were

established. The first Baptist church in the Chin Hills was opened at Khuasak

village on February 17, 1906. Today, the Chins have the highest percentages of

Christian and literacy among other ethnic groups in Myanmar. The Chin Hills, a

mission field in the past, now has become a sending church.[15]

By: Victor Aung Thu Lin

[1] Thawng

Khuo Tuong,

“Weaving A Contextual Theology of Mission For Myanmar” (D.Miss diss.,

Philippine Christian University, Manila, 2012), 1.

[2] Gustavo

Gutierrez, The Power of the Poor in History:

Selected Writings. Trans, Robert R

Barr, (Maryknoll,

NY: Orbis, Book, 1983), 17.

[3] Curt

Cadorette, From the Heart of the People:

The Theology of Gutierrez (New York: Meyer-Stone Books, 1988), 18.

[4] Gustavo

Gutierrez, The Power of the Poor in History:

Selected Writings. Trans, Robert R

Barr, (Maryknoll,

NY: Orbis, Book, 1983), 119.

[5] Alan B. Cabas, “A Theology of Creation of Informed by Mayaw Belief” (M.Th thesis, Union Theological

Seminary, Philippines, 2017), 23-24.

[6] Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology

of Liberation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1973), 176.

[7] Lionel Landry, The Land and

People of Burma (New York: J.B Lippincott Company, 1968), 60.

[8] Chao-Tzang Vawnghwe & Lian H. Sakhong, eds., The Fourth Initial Draft of the Future Chin-land constitution

(Thailand: Chaing Mai, UNLD Press, 2003), 24.

[9] Ibid., 57.

[10]

[12] Donald M. Seekins,

Historical

Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar) (Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006), 2.

[13] Roger Bischoff, Buddhism in

Myanmar a Short History (Kendy, SriLinka: Buddhish Publication Society

1995), 17.

[14] Terrence W.

Tilley, The Evils of Theodicy (Wipf and Stock Publishers:

Georgetown University Press, 2000), 7.

[15] Lian H. Dohkam,

“The God Above All: Khuazing-Pathian

Discourse as Point of Departure for Theologizing in the Chin Context” (Ph.D

diss, Philippine Christian University: Manila, 2008), 25-27.

Comments

Post a Comment